The Medium is the Message: Keys to Media Consciousness

Recognise the Effects of Technology

This could have been written yesterday. That was my thought as I began making my way, now for the second time, through Marshall McLuhan’s Understanding Media. But the book was published in 1964. By the time I read it, the year 2000 had come and gone. How had this man - who had never seen a personal computer - written with such perception of a world so lately conceived?

It was this strange prescience, this clarity of vision, that earned McLuhan the title of prophet for the Internet Age. And like other prophets, what he saw clearly he expressed often darkly. Speaking in aphorism, myth, and metaphor, McLuhan garnered much in the way of superficial attention but far too little in lasting awareness.

That needs to change. Overwhelmed as we are by a flood of new devices and technology, we’ll need a life-boat if we hope to avoid drowning. Understanding media will give us the tools we need to find bottom and, hopefully, to chart a better course.

In this article, I will introduce McLuhan’s most famous aphorism and break it down piece by piece. By the time you finish reading you’ll have a new understanding of the high stakes game we play each time a new gadget is introduced.

The Medium is the Message

You’ve probably heard these words before, but if you’re like most you haven’t spent too much time thinking about them, and you aren’t entirely sure you know what they mean.

That’s something we can fix: let’s dive in.

What is a Medium?

Now what I’m about to say might be obvious to you, but bear with me a moment for the sake of those who might not have noticed. We are so used to saying media as a sort of mass noun that we forget that the word comes from a plural form. The singular is medium, a Latin noun meaning middle.

The middle is what comes between one thing and another. This is vital, and from now on when you say or hear the word media, I want you to think of it as what comes between. For example, your phone is a medium. It comes between you and the person to whom you are speaking. It bridges the gap. All communications media are bridges for our speech, text, and images.

You can also think of a medium as a tool. A tool stands in the middle, that is, between you and the results you hope to accomplish with it. If you are an artist, you might think of your medium as paint. That is, paint is what comes between your audience and the picture in your mind’s eye.

But it’s not only the paint. It’s also your canvas and paintbrush. There is a big difference between a child’s finger-painting and the fine-brushwork of an accomplished master.

Now maybe you’ve begun to see where this is going and your mind is rushing full-speed ahead. You’ve realized the medium itself is not just a transparent window on reality - as if we look straight through to a clear vision of what it represents. No, we are not looking at reality, but its imitation in art. It is 2-dimensional, but your skill as an artist tricks us into seeing 3 dimensions where they don’t actually exist. The perspective is an illusion. What’s more, the surface of the canvas, the thickness of the paint, and the texture and direction of the brush-work all contribute something of their own. The medium of art presents us an experience altogether different from the more direct experience of our senses in nature.

But everyone knows that - it’s much too obvious! So you think. But what if it weren’t so obvious? What if there were a man who had never been outdoors? What if he were born in a museum, never setting foot outside to look at the sky or the ocean or the real live faces of other men and women? If you knew a man like that, living in total captivity to art, would you think him a prisoner?

Media, then, are not all clear windows between our eyes and far-off experience, but can also act like pictures painted on the inside walls of a prison-cell.

What is the Message?

The word message comes from a Latin root meaning send or sent. We think of a message as words being sent to someone too far away to speak to directly. We might use paper and ink to do this, but now we use e-mail or phone.

Without any media or technology, a message in ancient times would come in the form of a personal representative. A king might send an envoy or God might send a prophet. Or a mother might send a child to call the family for dinner. Thus human individuals acted as inter-mediaries, or media, before they were replaced by technology. The message came in human form, and his status or dignity spoke as much as the words he had to repeat.

When we think of modern media as distinct from its message, we are usually thinking about content: What does that book say? What is that Youtuber trying to tell us?

But this where we go wrong. What McLuhan taught us is that message and content are two entirely different things. Content is what we pay most attention to, and it hardly needs to be explained. We naturally want to know what a movie is about. We want to know what was on the news last night.

But these details are not the message. The message we are missing is the one attached to the form of its delivery - the technology itself. It should be obvious, but the fact is we’ve allowed ourselves to be so hypnotized, so entranced by our media that we are barely aware of its real effects. The message is hidden in plain sight. It is all around us every day, but it escapes our notice just as water escapes the notice of a fish.

If we wish to see ourselves as we are, we’ll need to start from an outside point of view. So strip away, if you will, all the assumptions of modern life. Imagine a primitive tribe living deep in the Amazon rainforest. You are now one of them. You’ve never seen a cell phone or a screen. You can’t read or write and you don’t even know what a book is. You live only in the here and now. The past is a mystery almost as much as the future is. You neither know nor care about what might be happening outside the direct experience of your tribe.

Now by some strange chance you are suddenly transported to another world - a strange world where men and women sit alone, staring into glowing lights, barely moving for hours on end. You can’t see what they see, but you wonder what it is that so fascinates them. They don’t go out, they don’t speak to each other, except once in a while an odd sort of wheeled boat rolls up outside one of their great houses, and then a man gets out, silently drops a box by the door, and then beats a hasty retreat.

You think to yourself, These people must be crazy!

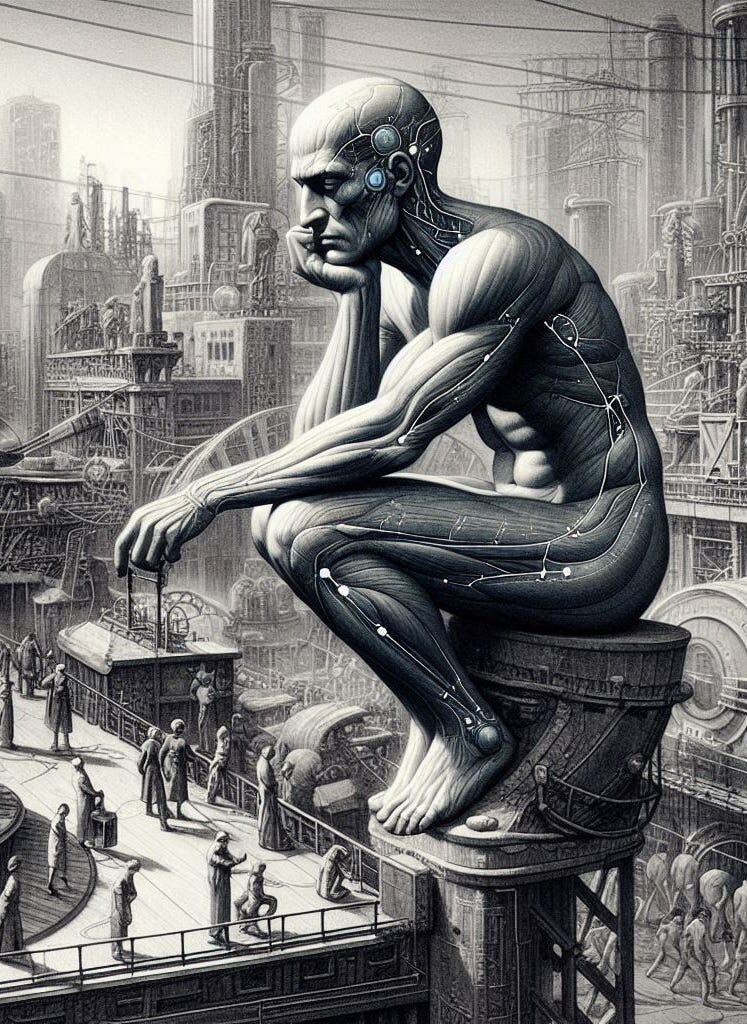

Standing at a distance you begin to see that everything about the way we live our lives is changed, transformed, and often deformed, not by what we see on the screen - not by its content - but by the screen itself. In the eyes of our Amazonian observer, we must look very much like our imaginary man in the museum: prisoners of our own art.

This state of affairs is exactly what McLuhan alluded to in his famous aphorism. He made it crystal clear with the following definition:

"The message of a medium or technology is the change of scale or pace or pattern it introduces into human affairs."

It is impossible to introduce any medium or tool or technology into our lives without at the same time transforming them. But there is hope that, in cultivating greater awareness, we might in some ways defend ourselves against a fatal outcome.

There is an old story, one McLuhan himself liked to use. In the ancient Greek myth of Narcissus, the young man saw his own reflection, for the very first time, in a clear pool of water. We tend to laugh when he hear this story - how absurd that Narcissus should fall in love with himself. But the point we miss is that Narcissus did not understand what it was he was looking at. He didn’t know that what he saw was just a reflection, and he didn’t know it was only his own image that had him so transfixed.

From that time on Narcissus never moved from the spot. Some say he withered away in despair, others that he tried to embrace the illusion and drowned in the attempt.

This was meant as a warning to us. For have we not, as a society, been transfixed by a fascinating but distorted reflection of the whole social life of our people? And are we not, like Narcissus, slowly withering away as we gaze at a lifeless image that can never return our embrace?