When Yours is the Only Real Face in the Room

Main Character Syndrome in C.S. Lewis' Little-Known Novel

“Some say the loving and the devouring are all the same thing.”

– Ungit’s priest

What if our deepest expressions of love are merely a disguise for something darker? How often is our care for others only a cloak for self-interest – a jealousy we refuse to acknowledge, working beneath the surface to the pain and confusion of those we hold dear?

Do we ever truly love others for their own sakes, or do we only love the roles they play in the stories we write for ourselves?

Till We Have Faces: A Review

I just finished reading C.S. Lewis’ Till We Have Faces, and these are some of the questions that came to mind while I was reading it. This is not one of Lewis’ more popular books, and I’d never heard much about it. But I’ve had a copy sitting on the shelf for years and always wondered what it was about. After an arduous slog through 900 pages of E.P. Thompson, I was looking for something lighter, and that’s when I finally decided to give it a read.

It turns out that Till We Have Faces is a retelling of the ancient Greek myth of Cupid and Psyche. If you’ve never heard it, the story involves three sisters, one of whom was extraordinarily beautiful. In fact, Psyche was so beautiful that the goddess Venus herself – that’s Cupid’s mother – was jealous. As the story goes, Cupid accidentally pricked himself with his own arrow when he saw Psyche, and proceeded to fall in love with her. He then takes her away to live in his palace as his wife. But Cupid imposes one very important condition: Psyche is never allowed to see his face. He comes to her only at night, and always flies away before morning.

But her two sisters are jealous, and they persuade Psyche to take a candle and look at his face while he is asleep. As you might expect, the results are tragic, as they usually are in Greek myths about women and impulsive curiosity. A drop of hot wax falls on Cupid’s face, and he wakes up and flies away for good. There is more to the story, but I’ll leave it at that.

Perspective Shift: Psyche’s Sister

Now, this book is not just a simple retelling of an old story. Lewis has completely transformed and re-imagined his source material to such an extent that reading Till We Have Faces is more like crossing the path of the old myth than traveling along the same road. We do encounter characters and events from the original, but the narrative context and perspective are completely altered. In the first place, it doesn’t take place in Greece or among the Greek gods, and the main character is neither Cupid nor Psyche, but Psyche’s ugly stepsister. The whole book is written from her point of view in the first person, and I have to say it does an excellent job of subverting the reader’s expectations.

It naturally begins by engaging the reader’s sympathy with the protagonist. We’re sucked in by the early childhood memories, while being introduced to a strange, hostile, and pagan world. Orual is the woman’s name, and she is one of the daughters of the king of Glome – a violent man of mercurial temper. We also meet the priest of the temple cult of the goddess Ungit. You can probably tell by the name Ungit that the religion portrayed is a very ugly one. Orual describes it in oppressive terms, complaining of the darkness and what she calls the stench of holiness. This goddess, Ungit, is supposed to be the equivalent of the Greek Aphrodite or the Roman Venus.

And we aren’t left guessing about that aspect of the goddess’ identity. One of the main characters is a Greek slave nicknamed “the Fox”, who serves as tutor to Orual and her sisters. He makes the connection early on. And this is where it gets interesting: the Fox is a disciple of the philosophers, and he completely rejects the traditional pagan myths, referring them, like Plato, to the lies of Homer and other old poets. So he teaches the girls a sort of stoicism, skeptical of cultic superstition. We, as modern readers, naturally fall in with this as being obviously superior to the amoral and grotesque rites of paganism.

That’s the set-up.

Beauty and the Beast

What Lewis does with the story after this serves progressively to subvert and undermine the reader’s expectations and prejudice. As the story unfolds, we begin to realize that the protagonist is not only ugly on the outside, but on the inside as well. This correspondence of character and appearance naturally accords with the conventions of traditional story-telling, but it goes against a favourite motif of more modern narratives – the conceit that those ill-favoured in the looks department tend to be endowed with inner beauty to compensate. On the other hand, the young and beautiful Psyche is lovely not only to look at, but in soul as well, kind and virtuous as a saint.

Meanwhile, the anti-traditional attitude inculcated by the Greek tutor is eroded as the cult of Ungit is revealed to be something other than mere priestcraft.

The major crisis comes fairly early in the story when the priest of Ungit demands a human sacrifice to appease the goddess. The whole kingdom of Glome is falling apart from famine, drought, and military and political problems. The priest tells the king that there is an accursed person in his palace who has angered the goddess, and as you might have guessed, it turns out to be the virtuous and beautiful Psyche, who has provoked Ungit’s jealousy by her beauty, which was so stunning that people sometimes worshiped her as if she were a goddess herself.

As dramatic as that sounds, the pivotal conflict comes about after these events, when Orual goes to retrieve the remains of Psyche’s body from the sacrificial tree. It turns out that the body has disappeared without a trace. Orual then goes exploring the nearby mountain, and to her surprise she finds Psyche there, alive and well. Psyche tells her that instead of being killed by the mythical shadowbrute, she had been taken as a bride by Ungit’s son, the god of the mountain. She says she lives in a beautiful palace and that everything is wonderful. The only problem is that no one else can see this palace, and Psyche appears to be living in rags out in the open. What’s more, the god only comes to her at night, and she is not allowed to see his face. Orual thinks she’s raving.

I won’t give it all away here, but this conflict between the world that Psyche sees and the world inhabited by here sister Orual sets up a tension that pervades the whole book. Psyche’s fantastic story challenges Orual’s philosophical beliefs, and from here on in you see this cloud of doubt and ambiguity fill the protagonist’s mind as she falls into a pattern of delusional rationalizations. But because the book is written from her perspective, the reader is left to recognize what Orual does not. We have her thoughts as she gives them in what, to her, seem reasonable terms. But the reader will easily see the narrator’s dishonesty.

This was one of the book’s strong points, and I enjoyed the inside view of the protagonist’s self-deception. It was a good occasion to reflect on our very human tendency to delude ourselves, and to disguise selfishness as love. Orual pretends to virtue even as she allows her jealousy to destroy the object of her affection. Throughout the book, the pattern we see in Orual and her various relationships is in fact a sort of Narcissism: her love for others is only a form of self-love. Friends and family are little more than extensions of her own ego, mere props in the construction of her own sense of identity. She is not able to desire the good of others when it conflicts with her own desire to possess them for herself.

The Book within the Book

Lewis adds an extra layer of immersion to his story-telling by incorporating the book itself into the structure of the story. His use of the first-person is not just a stylistic choice; rather, the narrative as it comes to us is wrapped up as an object within the story: a book written by the protagonist in response to the trials of her life, and in which she becomes the main character of a story that once belonged to another.

Orual finds the pressure of events too great to maintain her philosophical composure, and in its place she adopts an antagonistic stance, not simply toward superstition as such, but toward the gods themselves. The book represents her account of the gods’ injustice toward her, and she fills its pages with complaints about their refusal to reveal themselves in a clear, unambiguous way. And even when her own jealousy brings her sister to ruin, she blames the gods for leaving her in doubt about what to do. Events have fallen out such that she can no longer disbelieve in the gods, but she still can’t decide exactly what to believe about them. The only thing she’s sure of is that they are unjust and she hates them.

A Look in the Mirror: Advent of Self-Awareness

This conflict comes to a head as the book wraps up. Toward the end of her life, as Orual reviews the book she’s written, she has a series of epiphanies and begins to lose confidence in her own complaints. She starts to see in herself an image of the very thing she hates: the goddess Ungit with her consuming jealousy. She realizes that she’s made sacrifice of other people’s lives in service to her own desires.

At this point, much of what was only implicit or suggested by the narrative becomes explicit. Lewis doesn’t leave us guessing about what he wants us to see as the protagonist turns a critical eye on herself, and in a flourish of bracing self-honesty she re-evaluates her entire life.

Likewise the supernatural elements come up for review, leaving ambiguity behind in favour of more transparent allegorizing. For much of the book, the comparison of Christianity to paganism remains implicit. Lewis draws some attention to what he is attempting to do, but the touch is relatively light until the very end. The earliest hint comes in the words of Ungit’s priest when he demands the sacrifice of Psyche. The reason for the sacrifice is that Psyche has ostensibly angered the goddess – she is accursed and must be given over to purge the guilt from the kingdom.

To stop the plagues, the accursed one must be bound to a tree and left to be devoured by the “shadowbrute”. When the king suggests they sacrifice a thief instead, the priest tells him that such a substitute is unacceptable, for “in the Great Offering the victim must be perfect.” It’s then suggested that the victim goes to be the bride of the goddess’s son, the god of the mountain who sometimes appears in shadowy form. Thus her fate is really a blessed one. When the Fox objects to this seeming contradiction, the priest responds, “Why should not the Accursed be both the best and the worst?” Taken together, the allusions to the crucifixion are plain enough.

But Psyche isn’t the only figure given an allegorical significance. The god of the mountain is made to resemble Christ through the theme of the sacred marriage, and Psyche is the believer who knows the blessings of union with the divine, exciting the jealousy and disbelief of those she’s left behind. Significantly, Ungit’s son is never named in the book. He is never called Eros or Cupid, but simply referred to as “the god of the mountain”. Lewis’ intent with that omission is to leave the god’s identity open to question, and indeed, when he speaks briefly to Orual near the story’s end, she replies, like Paul on the way to Damascus, with the question: “Lord, who are you?”

Other Christian allusions appear at various points, including references to the resurrection, the Easter service, and the expulsion of man from the garden of Eden.

But the final chapters hand over the interpretive keys:

“All, even Psyche, are born into the house of Ungit. And all must get free from her. Or say that Ungit in each must bear Ungit’s son and die in childbed – or change. And now Psyche must go down into the deadlands to get beauty in a casket from the Queen of the Deadlands, from death herself; and bring it back to give it to Ungit so that Ungit will become beautiful.”

Ungit then is the fallen Eve, the mother of all whose lusts consume the human race, the woman whose aspirations to godhood gave us our first example of “main character syndrome”, along with its most tragic consequences. But Ungit’s son is the seed of the woman, the beautiful Christ whose birth in each brings death to the sinful nature. Psyche is also Christ, whose journey to the underworld returns “beauty in a casket”, spiritual life, to the deformity of Eve and her children.

This refracted symbolism, the several characters representing different things in different relationships, is captured in the Fox’s pantheistic platitude: “Men, and gods, flow in and out and mingle.” Lewis’ approach is a blend of allegory and allusion, and in the second respect owes something to the conception of the Christian story as the world’s “true myth”, the one to which all other myths point in fragmentary and shadowy fashion – an idea impressed on the author by his friend, J.R.R. Tolkien.

Merits and Missteps: An Evaluation

With all that said, the question remains: Is Till We Have Faces worth reading? What did Lewis manage to achieve, and where does the story fall short?

First I’ll say that I did enjoy the book. It was an easy read and a made a nice break from the denser nonfiction I’ve been reading lately. The writing style doesn’t make any heavy demands on the reader, while the quality of the narrative still invites thoughtful engagement. The fact that the reader is allowed to perceive things about the protagonist to which she herself is blind is a good draw, serving also as an invitation to self-reflect. What lies do we tell ourselves in order to justify our actions? Do we disguise self-seeking as love for others?

The religious ambiguities and hints of allegory add a good deal of interest, and I wanted to keep reading to find out where the author was going with it.

The characters in the book were well-drawn, not especially deep, but evoking familiar archetypes. The protagonist was compelling if not likeable, and Lewis’ portrayal of her rationalizing tendency had enough psychological realism to be convincing.

The dialogue was okay for the most part, but a few exchanges fell flat and took me out of the story. And as often happens in fiction, characters’ speeches sometimes read more like the thing you wish you’d said than what you actually said.

The story itself was well-constructed and satisfying overall. However, some of Lewis’ choices raised an eyebrow – there was a dubious element of woman-warrioring which struck me as highly unlikely. However, it did serve purpose within the narrative and as character-development: you can sort of imagine the woman so ugly no man could love her, determined to take on a more masculine role in her own life and relationships. After the death of her father, Orual becomes queen in the absence of a male heir, and she ends up ruling and leading the country into great success. Lewis was a man writing a female lead, and toward the end of the book it does begin to show through.

The story’s conclusion involves the protagonist in a series of epiphanies, self-reflections, and religious speculations bordering on the didactic. What was left under the surface for the reader to observe and interpret is all brought into the foreground and easily laid out for anyone familiar with the Bible. Critics might class this as a literary sin, but in my view it wouldn’t be fair to call it a total failure. It does link in with the narrative as a whole, answering or recapitulating questions with which the protagonist has been grappling in her mind from the beginning. It works to an extent, although I do think Lewis cuts with too keen of an edge. He pushes too hard toward a Christian resolution for a story locked in a pagan context, going so far as to make the god of the mountain a stand-in for Jesus.

Beautiful Idols: A Warning

The way Lewis handles the relation of Christian and pagan religion is in many ways a reversal of the approach of modern critical scholars. In the twentieth century, it was a common attack vector against the faith to say that Christianity arose as a derivative of paganism, just another variation of the mystery cults gaining popularity within the Roman Empire.

Notable Christian scholars like J. Gresham Machen countered these claims by closely examining the chronology and historical source material. But Lewis takes an approach that simply bypasses the critiques of comparative religion. *Of course* there are resemblances between paganism and Christianity – we all inhabit the same universe, and it stands to reason that falsehood must bear some resemblance to truth if it attempts to satisfy an impulse toward personal religion.

Lewis stands the critics on their heads by treating pagan myth as a shadowy approach to faith. And while Lewis does also highlight some of the uglier aspects of idol worship, the limitations of the story’s context prevent any unambiguous separation of the good from the evil. As such, his attempt to trace a redemptive arc for the protagonist runs up against the danger of appearing to redeem the idols themselves, in particular the god of the mountain as he takes the place of Christ.

Here it’s important to remember that Christianity is not an abstract faith. It is personal, and Jesus is a personal God, not a mere manifestation of deity. As such, there is danger in Lewis’ approach, insofar as it takes the glory of Christ and transfers it, in some measure, to an idol.

If we read Till We Have Faces, and other stories like it, we ought to keep in mind the words of the commandment, “I the Lord thy God am a jealous God,” and further, “I will not give my glory to another.” The problem with idolatry is not simply that it represents the wrong system of religious truth – it’s that it turns us away from the Lord Himself to love others in His place. Hence the prophets’ rebuke to Israel, that they went “whoring” after other gods. Eros, Cupid – “the god of the mountain” – is not Jesus. Aslan the lion is not Jesus.

And while I’m not prepared to condemn this genre of fiction in its entirety – we do have allegories and types of Christ in the Bible, and it is true that both men and angels are, in their own way, reflections of God’s glory – I do think some of these books cross the border from illustrative parallel into equivocal territory. The Christian reader may glean insights from them, but with a strong caution not to be drawn away to beautiful idols in the false belief that they are just another form of God.

Final Verdict and Closing thoughts

At best, Till We Have Faces is a book to pick up second-hand if you find it. It’s not a masterpiece by any stretch. But with some caveats, it’s worth a read if you’re looking for something lighter. I will say that I don’t recommend it for younger readers or the immature. While the content is not obscene, the sexual themes and the way Lewis handles his religious message make it unsuitable for children.

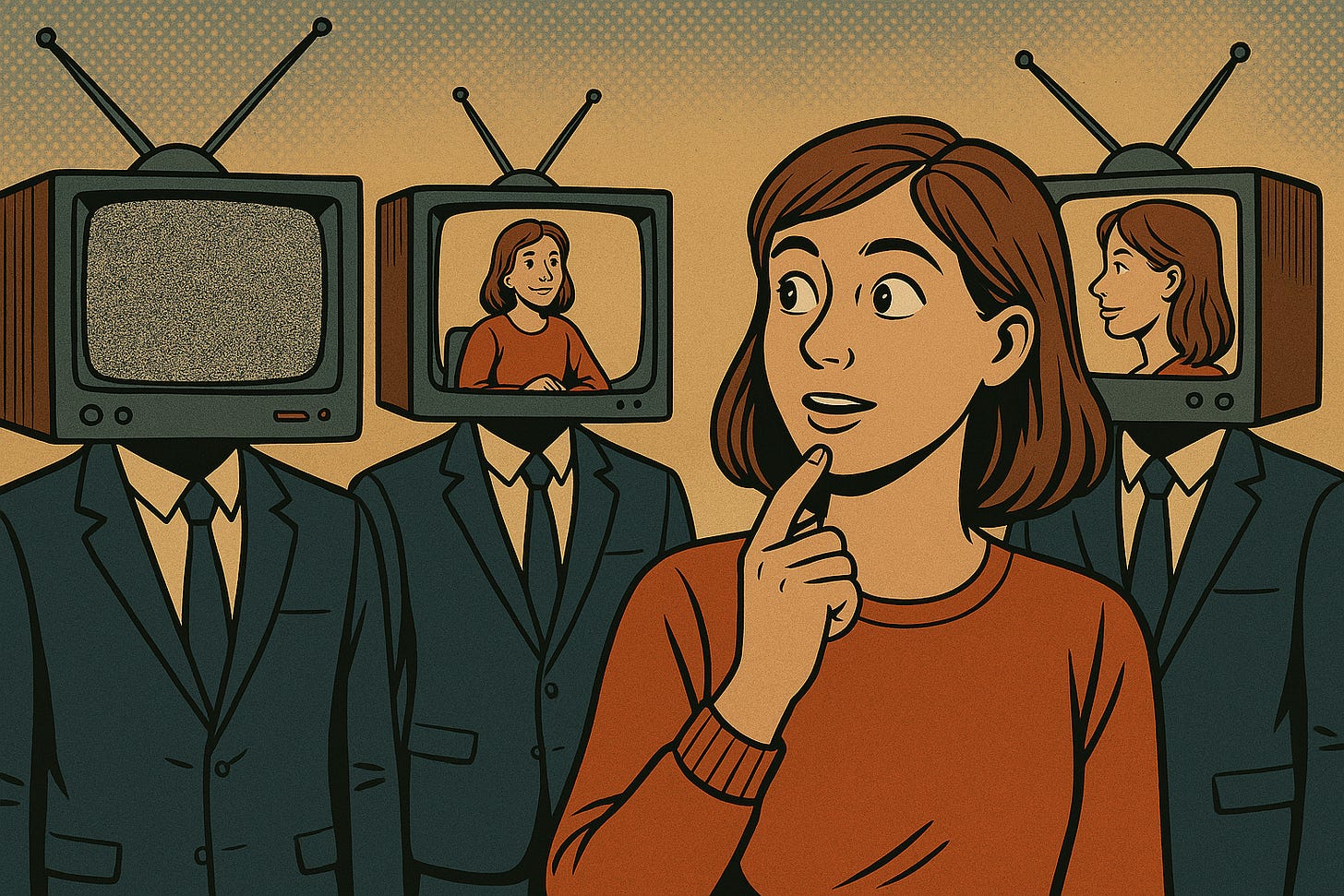

It is a decent novel overall, offering some worthwhile insights into human psychology. Through Orual's self-deception, Lewis holds up a mirror to the lately named "main character syndrome." In her solipsistic world, Orual constrains others to play no more than supporting roles in her own personal drama, denying them agency in their own stories. Though originally just a bit-player in the myth of Psyche, Orual's narrative reshapes everything to revolve around herself.

The book’s warning has never been more relevant. We now live in a digital landscape where everything is tailored to individual preference and subjective desire: algorithmic feeds deliver exactly what our lizard-brains crave, while we swipe through potential mates as if they were products for our consumption. The personalized and performative world of social media fuels delusion and fosters neglect of one fundamental truth: it’s not about you. It’s not about me. Others have their own stories to live.

McLuhan taught us that media are extensions of the self. Thus the absorption of social life by technology reduces relationship to an egocentric appendage.

Perhaps the greatest danger of our AI-mediated world is that as we increasingly converse with machines as if they were human, we begin to treat humans more like machines – supporting characters with no internal direction of their own. When our brains can no longer distinguish between the authentic and the artificial, we unconsciously devalue the interactions that once offered us unmistakable evidence of psyches not our own.

Modern Western society has already separated the individual from traditional community bonds through the combined power of technology, commerce, and changing social paradigms. Artificial intelligence threatens to accelerate this alienation, as each one of us constructs a private universe with himself at the centre. The digital face we present to the world becomes the only reality we know as the inner lives of other faces dissolve in a sea of doubt.

As communal life continues to erode in the acid bath of technological solipsism, the danger of self-absorption can only increase. With this in view, it’s never been more important to remember that none of us is the main character in the world’s grand scheme, and we can only know our true identities – our real faces – as we accept our supporting roles in the divine narrative of God’s eternal kingdom.

Left on the Cutting Room Floor:

“Holy wisdom is not clear and thin like water, but thick and dark like blood” – Ungit’s priest

This creeping solipsism of the screen has invaded daily life, and time spent together is now passed behind the voiceless, faceless mask of the text message. After the widespread adoption of smartphones, teachers began to report that empathy among children dropped markedly. Even with coaxing, students struggled to appreciate the effects of their actions on the others.

In the Works:

Technology and the Tower of Babel

Booksmaxxing: Why and How to Collect Physical Books

Intentional Communities in an AI Age: Why We Need Them Now More than Ever

Current Reading:

A Theology of Nature, Ruben Alvarado

The Relentless Revolution, Joyce Appleby